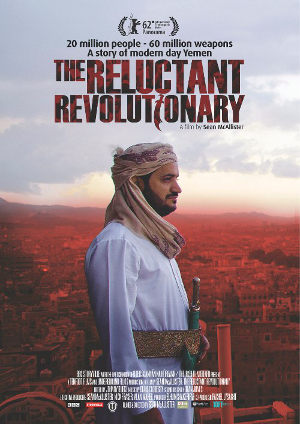

The Reluctant Revolutionary

© Comment Middle East / April 04, 2012

When British film maker Sean McAllister set out to chart the decline of Tourism in Yemen, he could not have predicted that within a few months the country would be submerged in a full scale popular uprising. And yet his documentary is not an attempt to explain the dynamics of the Yemeni revolution, rather like all good documentaries it is primarily a character focused piece, managing to tell the story of many through one.

When British film maker Sean McAllister set out to chart the decline of Tourism in Yemen, he could not have predicted that within a few months the country would be submerged in a full scale popular uprising. And yet his documentary is not an attempt to explain the dynamics of the Yemeni revolution, rather like all good documentaries it is primarily a character focused piece, managing to tell the story of many through one.

There has seldom been as compelling a subject as Qais, the eponymous reluctant revolutionary. A tour guide in a country almost entirely bereft of tourists yet still humorous and endearing there is an inescapable element of tragicomedy about his story which McAllister’s unfussy camera work allows to take centre stage.

The beauty of Qais’s transition from skeptic to vocal supporter of the revolution is the immediacy of its relevance, not just to the Yemeni uprising. He, like so many across the region’s uprising populaces must balance the struggles of his own life, business and family with that of his people’s fight for dignity and human rights. The greatest achievement of this documentary is one which has largely alluded the cameras of the mainstream media, namely managing to truly capture the Arab Spring at the level of the ordinary individual. We at once understand Qais’s hesitancy to join the uprising with the inevitable chaos and instability it will cause him personally, already scarcely capable of sustaining his own family and business. Simultaneously it allows us to appreciate the stakes involved when his hesitancy begins to give way to resolve, placing his marriage and ultimately his own life on the line, unable to sit idly by.

McAllister’s own presence throughout the film is both subtle and important. His simple yet unjudgemental style of questions allow us to hear the voice of what many will undoubtedly begin this film assuming to be a simple man. And yet like the majority of those featured in the documentary, his insights are at once greatly philosophical, boyishly humorous and profoundly melancholic. Qais’s remark, early on in the film, predicting the outcome of an uprising to be ‘not a bloodbath, but a blood-swimming pool’ is almost comical and yet as we find out later, tragically prophetic.

In The Reluctant Revolutionary, the Yemeni uprising serves as both a context to Qais’s own story and in its own right as a story of the dignity and bravery of the Yemeni people. The horrors of the regime’s brutal crackdown on Yemen’s staunchly peaceful protesters are documented by McAllister’s handheld camera. The scenes of shaky, cell-phone footage help lend a great relevance to the piece. This method of recording, made famous by Arab citizens charting their countries’ uprisings, embodies the chaos, confusion and fear felt by so many in the midst of these popular revolts.

The juxtaposing of ordinary life in the Arab worlds poorest nation with the extraordinary events of the Yemeni uprising and one mans personal journey through are what The Reluctant Revolutionary does so well and to great effect. It is the reluctance of the less politically inclined, the apathetic whose transitions have defined these revolutions, which form the heart of Sean McAllister’s documentary and ultimately make for a powerfully poetic testimony to the inspiring bravery of the ordinary citizens in the Arab Spring.

See the original review on the Comment Middle East website.

© Rosemarie Hugill / Doc Geeks

Even with its shortcomings The Reluctant Revolutionary is a very important and moving documentation of the Arab Spring. The extreme bravery not only shown by McAllister and Kais, but by every Yemini protesters is extremely inspirational and admirable. The film is an ode to investigative journalism and the inspirational will-power of the Yemini people who don’t take no for an answer.

© The Scotsman / March 19, 2012

The shadow of mortality also hangs over the Storyville documentary, THE RELUCTANT REVOLUTIONARY, which, like Death Row, manages to find unlikely moments of black humour amidst its savage subject matter.

It stars Kais, a luckless tour guide based in Yemen, which, as home to al-Qaeda, can hardly be regarded as a tourist hot-spot. And yet when intrepid – and often terrified – filmmaker Sean McAllister first meets him, Kais appears to be in deep denial, not only about his personal fortunes, but also about the need to revolt against Yemen’s corrupt government.

Cynical and world-weary, Kais wants no part of the simmering revolution. He seems more interested in chain smoking and chewing khat than taking to the streets. But as bitter unrest breaks out across the country, he gradually undergoes a dramatic change of heart, not least after the government starts to attack peaceful protests and kill its own people.

McAllister, who specialises in documentaries exploring the wider picture through the experiences of individuals, does an excellent job of chronicling the street-level energy of the Arab Spring, as well as the atrocities endured by people brave enough to challenge their oppressors. One chaotic scene in an overburdened hospital strewn with bodies is almost unbearable. Nevertheless, McAllister’s often shocking film is vital in exposing the brutal realities of this historic uprising. But what price freedom?

© Cole Abaius / Film School Rejects / February 15, 2012

After last year’s Arab Spring, there will undoubtedly be a host of documentaries and narrative projects with Middle Eastern revolution chanting from their cores. It will be interesting to see how well they stack up against The Reluctant Revolutionary because it should be considered the standard. Sean McAllister’s tennis-shoes-on-the-ground doc is unexpected in its storytelling and unflinching in its display of the mass murders that cemented the people of Yemen against their leader, Ali Abdullah Saleh.

But this story doesn’t start with crowds shouting from tents. It starts with a tour guide named Kais who can only see his business dwindling because of some disgruntled citizens. He’s actively against the revolution for that pragmatic reason, but even as his professional life deteriorates, his understanding and support of the movement dramatically shifts his opinions.

The second greatest strength of the film might be McAllister’s disarming presence. Normally a documentarian that shoves him or herself in front of the camera comes off as desperate for attention and willing to sabotage his or her own story in the hopes of getting some screen time. McAllister’s first few scenes come off a bit like that, but further down the dusty road it becomes clear that he had to include those early moments as a set up for when the Yemeni government forces him to become a part of the story he’s trying to film. Why he wasn’t on a plane back to the safety of his home after being targeted by the secret police is anyone’s guess, but it’s a damned good thing he stuck around because the footage he got is not just fascinating – it’s vital.

Of course, it’s really Kais – the frustrated yet warm Yemeni man – that anchors the entire project. He’s a sweet figure, one that is strongly opinionated, quick with a joke and struggling with economics and emotions. He’s trying to do the right thing toward his business and family, but doing so seems about as worthwhile as shoving his head into the ground. The ornate hotel he used to run has fallen into ruin, and his only avenue for money is the withering tourism business that was anemic even before people started gathering in the streets. His wife is threatening to leave, he has to borrow money to buy them a few days’ worth of food, and he’s convinced that the movement everyone puts stock in will fizzle out like all the others did before.

Kais, with his cheek full of a leafy drug called khat, looks like a chipmunk trying to smuggle a baseball but his sunken eyes belie a more serious man. Without him, there is no movie.

The introduction of Kais into the blocks that the rebels have occupied slowly wins him over, and McAllister’s constant questions (which come of as genuine and naively Western) force the issue of revolution into the mind of a man unwilling to join the cause.

Then the violence gets worse, and like many of his neighbors, Kais chooses to become a new element of the growing crowd.

McAllister finds himself in places cameras just aren’t meant to go. The plainclothes cops of Yemen who try to infiltrate the movement are highly interested in him, but he and Kais lie daily to protect his status as a harmless tourist. To them, he’s a teacher, but it’s a protected status that won’t last forever. When five journalists are deported, it’s a sign that something huge is going to happen.

Words, with as much faith as they’ve built up over the centuries, are useless in the context of what the movie shows next. The bittersweet nature of the story is blown away by the first explosions and rain of bullets, delivering a wide-eyed look at true violence and chaos. It was enough to make action movies look frivolous and insulting. McAllister captures the very thing the Yemeni authorities didn’t want him to capture, and it’s not easy to watch. Even tears seem like an inadequate response to the manic, screaming triage room that rings out with a terrifying, mortal urgency. The floors are smeared with the real blood of real men dying on screen. Nearby, a skull is caved in. A hole large enough to stick a finger into marks the neck of a man inches away from sucking in the last breath of his life. A 10-year-old boy lies limp on a cheap table. These are images that don’t fade away. Not from the mind and not from the heart.

McAllister has achieved something incredible here. The Reluctant Revolutionary is a stunningly humane portrait that shows vividly what’s at stake before leaving it bloody on the Formica floor of a battered concrete building. Fifty-two people died that day. The movement grew, Saleh left his office months later, but things are still burning in Yemen. This doc is the kind of Pulitzer Prize-winning work that boldly and at great risk to personal safety showcases how powerful media can be. It’s entertaining, yes, but it’s also film as indictment. Film as evidence. Film as historical document.

Through a smiling man with a face full of khat, McAllister has utilized a unique window into a world of personal pain and found the beating heart of a country paying in blood to be free.

See the original review on the Film School Rejects website.

© Deborah Young / The Hollywood Reporter / February 11, 2012

A breathless pace, a sense of black humor and a great central character make The Reluctant Revolutionary one of the most immediate and accessible descriptions of the Arab Spring yet to emerge. The place is Yemen and British documaker Sean McAllister (Liberace of Baghdad, Working for the Enemy) has the good fortune and sense of timing to be inside the country when the main events in Change Square happen, events that would lead eight months later to the resignation of president Ali Abdullah Saleh, dictator for 33 years. Colorful and easily understandable, it has the numbers to connect with Western TV viewers after it makes the fest rounds.

Travelling to Yemen on a tourist visa, McAllister spent months filming the country before the fateful events of the “Friday of Dignity” on March 18, 2011, when 52 peaceful protestors were shot to death by government agents. His constant companion and interface with Yemeni society is his utterly likable local tour operator Kais, an anxious 35-year-old father of three who works in his father’s travel agency. Beleaguered by creditors after the failure of a hotel venture, he at first blames the protest demonstrations for curbing the tourism that is his livelihood. But as events rapidly unfold around them and McAllister insists on filming in the capital city’s Change Square amid growing unrest, Kais swings to the other side. When he becomes an eyewitness to the Friday of Dignity massacre, he turns into a true believer in the revolution.

Many documentaries from the Arab world boast extraordinary I-was-there footage of the harrowing events of the Arab Spring and, being shot by local filmmakers, they show greater depth in explaining political events. What makes The Reluctant Revolutionary unique, however, is the central presence of Kais, whose cultural openness and command of English makes him an ideal mediator between the Arab reality and the Western filmmaker. Together with McAllister’s ability to capture the irony and sheer paradox of situations, he pulls the viewer into the action with his marital problems and nervous chewing of the local drug Khat.

McAllister acts as his own cameraman, and the only real problem is his choice to film with a constantly moving and zooming handheld camera, whose net result looks like a cell phone video. Though the one time he’s shown filming he is holding his small DV cam perfectly still, there is practically no shot that is held steady long enough to be fully absorbed. This would seem to be a stylistic choice rather than a technical necessity, because even in quiet indoor situations the extreme close-ups are nervously jumpy. It all imparts a dynamic, exciting look to the film, but comes with the cost of denying the viewer a badly needed visual breather to think things through.

See the original review on The Hollywood Reporter website.

© Mark Cosgrove, The Huffington Post / February 22, 2012

Sean McAllister’s The Reluctant Revolutionary follows Kais, a tourist guide in Yemen, as the revolution unfolds. His work is already perilous and drying up because of the Taliban and when a protest camp sets up in ‘Change Square’ in Yemen’s capital Sana’a, Kais is non-committal partly feeling this is bad for tourism. Over time he begins to get involved and engaged. Film-maker McAllister is either a fool or brave or possibly both because he is obviously the only foreigner around, wondering in a volatile environment with secret police mingling amongst the crowds of protesters. What he captures is extraordinary with access conventional media flinch from. When the state troops shoot into the crowds the camera follows Kais into the makeshift hospitals. The scenes are devastating. But the mood of change and resilience is evident as it is in the charming reluctant revolutionary Kais.

Read about The Reluctant Revolutionary