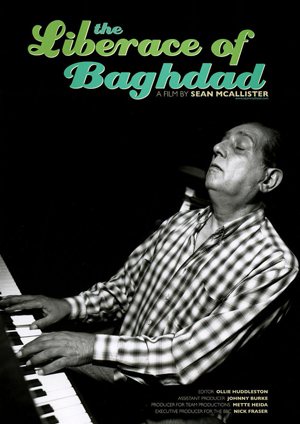

The Liberace Of Baghdad

© Denis Seguin / Screen International / March 22, 2005

A documentary that goes behind the daily headlines out of Iraq, The Liberace Of Baghdad focuses on a pianist whose professional career came to an abrupt end with the toppling of Saddam. Shot over eight months in Baghdad in 2004 at tremendous peril to its director Sean McAllister, not to mention his subject, the film provides a vital insight into the impact on civilian life of the US-led invasion and occupation.

A documentary that goes behind the daily headlines out of Iraq, The Liberace Of Baghdad focuses on a pianist whose professional career came to an abrupt end with the toppling of Saddam. Shot over eight months in Baghdad in 2004 at tremendous peril to its director Sean McAllister, not to mention his subject, the film provides a vital insight into the impact on civilian life of the US-led invasion and occupation.

The film, which premiered at Sheffield International Documentary Festival in November 2004, won a special jury prize at Sundance this year after screening in the newly-launched World Documentary Competition. While continued festival play is assured, the film’s international theatrical prospects – it has already aired on the BBC in the UK – will depend on finding niche distributors who can lever the strong interest in Iraq and the high curiosity value of its idiosyncratic subject.

McAllister, whose 1998 documentary The Minders earned him the Royal Television Society’s award for best documentary, is the consummate documentary film-maker. Committed beyond the call of journalistic duty, his presence is very much a part of the film.

Sent on a recce to Iraq by the BBC to find a story about everyday life in Baghdad, he passed several fruitless weeks chasing leads, returning each evening to his hotel to chat with the pianist in the lounge. Soon, he realised the pianist was the story and ending up spending most of the year eating, drinking and bunking with him. The film is culled from 110 40-minute tapes, from which editor Ollie Huddleston has done a remarkable job of extracting a nicely focused 75 minutes.

Peter, a Christian Arab, left Iraq in his 20s to study piano in Italy. When he returned Saddam was in charge and was beginning hostilities against neighbouring Iran. Peter was forced to join the army, served on the front and killed. After demobilisation he returned to Baghdad, started a family (his wife, a doctor, delivered one of Saddam’s daughter) and slowly began to build a name as an instructor and performer. At his height he was earning $10,000 a month, enjoying a vast wardrobe and engaging in multiple affairs to the extent that his lavish lifestyle lead to the self-imposed moniker the Liberace of Baghdad.

The title puts the joke on Peter, especially for Western viewers for whom Liberace is better known as a camp

icon rather than a style-setter. Indeed, judging by his few performances in the film, Peter’s piano playing doesn’t correspond with his claims or his aspirations to be the “Chopin of Iraq”. But this only adds to the allure of this incongruous character with the hooded eyes and unfortunate pony-tail. With a cigarette perpetually between his lips, Peter proves a pragmatic guide to life during wartime: his mood, and hence the tone of the film, oscillates between bitingly satirical and deeply depressed. Forays to and from the hotel and Peter’s suburban home continually darken that tone: a suicide bomb’s aftermath forces them to walk, leading to an impromptu encounter with a woman’s whose son is likely a victim of the attack.

Ironically, despite the promised liberation, Peter’s great desire is to leave Iraq for the US where his estranged wife and two of their four children reside. Meanwhile, McAllister spends time with the two adult children who have remained in Baghdad; the daughter is particularly vociferous about the failed promise of the US occupation and yearns for the days of Saddam. Her steely reserve is shattered by the death of a neighbour, murdered for working with a US company.

What sets the film apart is the rapport between journalist and subject – McAllister and Peter were on top of each other during the shooting, hunkering down against air raids – and the camera is very much an extension of McAllister with the viewer is along for the ride.

As the weeks pass, and the kidnappings and beheadings of foreigners escalates, the film begins to feel like all-too-real reality TV. It reaches a climax when the pair become lost on the drive to Peter’s house – street lights and traffic lights are things of the past – and end up in the no-man’s-land that is the airport highway. As the two men, with cracking voices, attempt to joke that this may be the end of the film, and McAllister cringes with his camera into the passenger seat, one can’t help doing the same.

© Jana Bennett / The Observer / Sunday, February 6, 2005

Independent film-maker Sean McAllister wandered into his Iraqi hotel bar, bored and frustrated that he was being prevented from making the film he had flown there to produce – about Saddam Hussein’s trial. Sitting at a piano, playing in this unlikely spot, was a former concert pianist. They struck up a conversation about the musician’s life, concerns, aspirations and family – two of his children were Saddam supporters and one wanted to be westernised. Sean quickly realised this was the story he wanted to tell, recognising that it encapsulated the tensions and contrasts of the realities of life in the war-torn country.

The result was The Liberace of Baghdad, which last week won a world cinema documentary prize at the Sundance Film Festival for BBC Four’s Storyville strand.

Here was a film-maker who was given the creative freedom and space to make the film he wanted, not exactly the one he had been commissioned to make – and was trusted by the BBC to deliver the best story he could for the audience.

© Denis Seguin / The Times / January 25, 2005

SAMIR PETER is frowning. The self-described “Liberace of Baghdad” has just learnt that Liberace is better remembered as a gay icon than as a pianist. He slugs Sean McAllister, the director of the BBC documentary The Liberace of Baghdad. “You said it,” says McAllister.

When they first sit down together, the two men make an unlikely pairing – the svelte Englishman and the woebegone Iraqi – but their rapport soon reflects the eight months they spent living in each other’s pocket in Baghdad where Peter – an apt surname for a Christian Arab – tickled the ivories in the hotel piano bar. That’s where they met, back in January 2004, when McAllister was on a three-week recce for the BBC‘s Storyville strand.

After Saddam’s capture by American forces, Storyville’s commissioning editor Nick Fraser was interested in a post-Saddam piece that would go behind the scenes to see how ordinary Iraqis live. McAllister, who earned kudos for the 1998 documentary The Minders, in which he turned his camera on the Iraqi government operatives who kept an eye on him during an assignment in the country, was the man for the job. But as the three weeks elapsed, McAllister was still looking for an angle.

“Each day I was going out looking for stories and each day I was coming back to the hotel and drinking wine with Samir,” he says. Which is when he realised that his story was sitting behind the piano.

To say that Samir Peter had led a rollercoaster existence would be giving too much credit to rollercoasters. None is so steep, none has such twists. The son of wealthy parents, he studied piano at a conservatory in Ancona, Italy, for three years until his money ran out. “I knew many Italian women,” he says, before embarking on a story about his first proper job as a “woman massager” and his time with a certain Signora Bianconi who took him in. A European tour ensued. He returned to Iraq shortly before Saddam took over leadership of the Baath Party and hence the country. Shortly after, Iraq declared war on Iran.

“I was at a party,” says Peter, recalling the first twist. “It was 6 o’clock in the morning.” Government agents, he says, were at the door, demanding that he accompany them to their headquarters. They forced him to “volunteer” for duty, and two weeks later he was in a Republican Army training camp. He served on the front and ending up stabbing to death an Iranian soldier, a deed he describes and indeed demonstrates in chilling detail.

On other details his memory is less precise: of the rest of his wartime service he refers vaguely to “friends” who engineered his exit from the army.

Returning to civilian life, he took up music instruction and started to build a name for himself as a concert pianist. His marriage to a doctor – she delivered one of Saddam’s daughters – yielded four children but little conjugal bliss. On the other hand, there was the Liberace reference.

“I had the same life,” Peter explains, “Many cars, many clothes. I had 350 shirts.” And many, many affairs. “Liberace means glamourous,” McAllister adds helpfully. “You’d have liked to be called ‘The Chopin of Iraq’.”

McAllister, listening to similar exploits at the piano bar, was taken by this contradiction at the keyboard, a man who looks much older than his 56 years, perhaps because of rather than in spite of the wispy ponytail. Whether or not his stories were all true, the facts were plain: the Americans were in Baghdad, Saddam was deposed and Peter, who once earned $10,000 a month, was divorced, penniless and living in a basement room of the hotel, hoping for a visa to America. McAllister pitched the story – “his country has been liberated and now he’s leaving” – and got the green light.

At first, subject and film-maker had differing views of what the film would be about. Peter says he agreed to participate in the film because he thought it would be about his music. But, he says, as weeks turned to months, and McAllister and his camera were constant companions, he started to reveal more and more personal details, and the film – as he says – “took a political turn”.

For McAllister the change came when he met Peter’s daughter – although his wife had left him taking two of their now-adult children, the other two, a son, Fahdi, and a daughter, Sahar, had remained, living in the family house. “When I met Sahar, that’s when it got really interesting. Her conflict with Samir really interested me.”

Like many Iraqis, Sahar initially welcomed the invasion, but after so many months of occupation she turned against the liberators. “Americans only make promises,” she says in the film. McAllister recalls a scene left out of the film – remarkable considering that he shot 140 40-minute tapes – a moment when he asks Peter why his daughter loves Saddam. “Samir said, ‘She doesn’t love Saddam. She loves her country.’ It’s hard for people outside Iraq to understand what it means for the Americans to be on Iraqi soil. It was unthinkable to me, having been three times before.”

Does Peter feel the American presence is a bad thing? “No. They want to rebuild the country. But the people of Saddam are still there and they are trying to stop them. Anyone who works with them, they kill them. Americans offer jobs but they are afraid to work with them. They have spies in the Green Zone.”

McAllister has no doubt. “Look, I didn’t go to Baghdad with a Michael Moore-agenda to nail the Americans.” Although he was against the invasion, he says, he went “with an open mind to see what was going on, and for about four months I was the butt of the jokes of other journalists. I was saying: ‘They’re rebuilding. Give it time. Give it time.’ But the more you see, the more you completely, utterly despair. It is a catastrophe beyond f****** belief. From small examples to big examples . . .” He shakes his head. “It’s ten years in the making. This film will be topical for ten years.”

As for Peter’s future, at the time of going to press he’s been out of Iraq for one month. He has his American visa – to attend the Sundance Film Festival, where the film had its world premiere – but the next steps are tentative. He will meet up with his former wife and wait for Sahar and Fahdi to join him from Jordan.

As for the home in Baghdad? Peter shrugs. “I locked the doors.” “His house-sitter was killed last week,” says McAllister. “On the street. Thirty years old, driving through a disturbance with the resistance. When the Americans get shot at, they just spray. A bullet hit him in the head and another hit the gas tank. He burnt to death. Thirty years old and two kids. The random danger of ordinary life.”

© Clairborne Smith / Sundance Insider / Sunday, January 23, 2005

British filmmaker Sean McAllister’s inroad to covering occupied Iraq arrived via the inscrutable logic of chance. Six months after the fall of Saddam Hussein, McAllister (Working for the Enemy) decided that it might be useful to go to Hotel Baghdad, amid the grenades and rocket launchers. “I wanted to make a film about what liberation meant for ordinary Iraqis,” McAllister explains at the beginning of The Liberace of Baghdad. He was then “led astray,” as he says in the film, by Samir Peter, a passionate, open-hearted Iraqi concert pianist who, in his heyday, earned $10,000 a month from his performances.

The viewer immediately senses that McAllister’s hunch to follow Peter rather than pursue his earlier, more sociological notion is the richer path. McAllister stumbled upon a telling family drama: Peter’s daughter supports Hussein, and she adamantly disagrees with her father, an unabashed admirer of America in a place where being tagged as a Western collaborator invites death. There is a world of commentary, as well as human interest, in the impatient sighs of their arguments.

“In the evenings I’d sit and have a drink,” McAllister said of the hotel where Peter had a room in the basement and would occasionally perform. “The tendency is for these people just to appear,” he said.”That’s what I’ve learned. Instead of going out to Falluja to find a story, it’s right there, really.”

Read about The Liberace Of Baghdad