Jude Calvert-Toulmin, May 2012

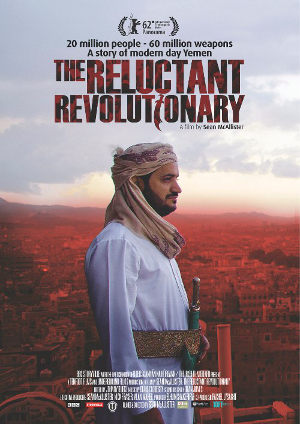

Sean McAllister – The Reluctant Revolutionary

On Sean’s ongoing determination to get a documentary about Syria commissioned: “I know the great British public are crying out to connect with these places through people instead of grainy you tube footage that just looks the same in the end.”

On Sean’s ongoing determination to get a documentary about Syria commissioned: “I know the great British public are crying out to connect with these places through people instead of grainy you tube footage that just looks the same in the end.”

“Sean McAllister he is one of the heroes in Yemen. Not just film maker. He is great film maker.” Kais, The Reluctant Revolutionary.

Sean McAllister is one of the most talented documentary filmmakers alive today. Winner of the 2005 Sundance World Cinema Special Jury Prize for Documentary for The Liberace of Baghdad, he continues to eschew mainstream high-budget documentary filmmaking and insists, with dogged determination, on following his own hunches and travelling the world alone in search of a good story built around a central figure battling for emotional and physical survival in unjust societies. If you want a quick taster of his filmmaking style, have a look at his Six Stories of Love and Hate, a short compilation of excerpts from some of his many award-winning films over the past 16 years.

Sean is currently touring film festivals worldwide with his film The Reluctant Revolutionary. This is his second interview with me; the first was an interview about his film Japan: A Story of Love and Hate.

Jude: Our last interview was about your film Japan: A Story of Love and Hate. Since then your documentary about the 2011 uprising in the Yemen, Yemen: Reluctant Revolutionary, which involved four trips to the country, has just been aired on BBC4’s Storyville, and you’ve been to Syria ten times working on a documentary over there. When did your fascination with Syria begin?

Sean: It began at the Sheffield Documentary film festival just after my Japan film premiere three years ago. At the time, I was making futile trips to Dubai looking for a film and wanted to find an alternative place to explore with more meaning. A Syrian guy called Nizam, who was resident in Norway, asked me a question so I went for a drink with him. To cut a very long story short (almost 2 years I guess) I ended up accompanying Nizam on trips back to his homeland, Syria, trying to make a film with him about his lost and confused life in the West. Sadly neither his mother nor Norwegian wife wanted to be filmed so I pursued the project anyway filming his family in Syria (Aleppo) but he was never really comfortable with the film, he was a film student at the time and much preferred being behind the camera with me I guess, so just as the BBC commissioned the film Nizam pulled out.

It was quite funny though because the BBC had wanted Dubai and I said no to it, then after 3 or 4 months of my looking in Syria they didn’t want Syria because they had done a 6 part series called “The Syrian School” and they didn’t think another Syrian film would grab a big enough audience.

But by then I had fallen in love with Damascus and was drawn back there. I remember getting a call and having Libya suggested randomly. Libya was far more difficult to enter at the time than Syria so I didn’t know what to do but fortunately Nizam was half Libyan (his dad was Libyan his mum Syrian) so when I went to pitch the Nizam film I told the commissioning editors that everyone was speaking in Libyan and the whole thing was shot in Libya – it was about telling them what they wanted to hear to get the commission I felt – I was pissed off that they wouldn’t commission Syria because it wasn’t in the news. They wanted Libya rather randomly because it had a sexier leader I guess.

Anyway after this fell through I went back to them with a great trailer to a film about a gay restaurant owner living just outside Homs in Syria – at this point (another 4/5 months later) they gave in I guess and just commissioned a film in Syria. He was a great fun character but on my first day back in Syria he pulled out on me, by which time I was desperate and could not afford to refuse the money so I never told the BBC.

Then one night in a famous Damascus park in the old city where young kids would gather to drink in the hot evenings (such was the openness of this attractive secular city) I met 45 year old Amer who was on the phone to his wife; later he told me she was in prison and had a phone in there with her. I began filming Amer who was a Palestinian living with no passport or legal rights in Syria with his wife Ragda an Alawite (from the President’s sect) – they had both met in prison some 13 years earlier, fallen in love and married on release and had 2 boys. Amer had given up his politics but Ragda couldn’t – she had written a book about their love story that attacked the Assad regime and it had landed her straight back in prison without trial. So for 4 months I filmed Amer’s life looking after the 13 year and 4 year old boys and living a life kind of on the run in Syria as he had no rights to stay without his wife who was the only one with a passport. He was also vocal against the regime in a way no one dare then – this was 9 months before any Arab spring.

I guess part of my journey with Amer was trying to understand the mind of someone so paranoid by a regime like Syria, I discovered he had lied about a few things to me; his wider family not being in Syria, him being a Christian not Muslim – when I confronted him he told me he had 2 stories to protect himself in Syria. I was a little pissed and left the country, it was 4 months away from my own family anyway and I felt it was time to go home. I decided to abandon Amer for now and to return to film confronting him on camera. I told him that if I returned he must tell me the truth and he promised to do so.

I remember heading home for Christmas 2009 feeling like I had no film. I’d been away for 4 months and was heading home to a frosty response. These are the dulls in what I do I guess and are the hard bits where one sacrifices so much time away and forgets about the issue of bringing money into the home, all for a film which sometimes doesn’t work out.

Anyway in the previous year in Syria I’d met 2 different people who’d told me about this guy in Yemen called Kais who ran this hotel. I remember sending him an email over Christmas, kind of desperate and him replying by chance, also kind of desperate as his hotel had gone under and he had no work (by now the Arab Spring was under way in Egypt in Tunisia and I sensed that Yemen could be next.)

But it was a funny, like I’d encountered in Japan when filming Naoki. I’d given up on him a year before and gone looking for a ‘better story’ that suited the ‘brief’ and ended up back in Yamagata by chance with someone else I was filming who had insisted I go to the Yamagata Film Festival with him, then when I arrived I met Naoki who was working in the festival. Towards the end of the festival this guy that I’d just got commissioned by the BBC and NHK pulled out on me and I was lost confused and Naoki was there and picked me up and almost started filming me. If felt right and appropriate to film him, like the experience had defined what the film should finally be.

I guess my arrival in Yemen was the same feeling – I felt an instantaneous connection with Kais and the experience had defined what and where the film should be. But it did leave a nagging question inside me for some time that I’d spent so long in Syria and come out with nothing and that I had unfinished business with Amer – I had left in a rush discovering his lies and, I guess, frustrated that nothing ever seemed to be happening actually in Syria – it was every country around Syria except Syria itself, and this was my problem in attracting an audience.

Anyway after Christmas and back in the Yemen I didn’t tell the BBC anything. They thought I was still filming the gay restaurant owner just outside Homs in Syria. I always depart from the commissioned story but never before have also departed country without permission. It was a big gamble that paid off. Had something bad happened needless to say I wasn’t insured and had no BBC back up and truthfully, had I tried to get permission, I doubt the film would ever have been made. I don’t think people felt Yemen was sexy enough. And Health and Safety just would not have gone with it I think.

By March 2010 I remember watching the news from my hotel in Yemen and hearing that protests had begun in Syria and I couldn’t believe it. Yemen was already on fire and much of my film was already filmed and then I got an email saying that my Syrian friend Amer and his young son Kaka 13 had been arrested in a central Damascus souk after protesting with pictures of the kids’ mother. They were released after 14 hours and I remember then making a call and Amer saying “Sean please come back we need you now more than ever”. I left Yemen for a break and could not get back in when violence had escalated and so I returned to Syria to meet up again with Amer. 2010 was spent visiting Syria on two trips for Channel 4 news who paid me to make 10 minute films as I couldn’t get my Syria film commissioned.

I remember my first meeting with the BBC before I’d told them anything about my story/country switch from Syria to Yemen. Nick Fraser entered the BBC screening room where I was due to show them something as another deadline for delivery was looming and they wanted me to meet this one. He said “Normally I ask you which story you’ve changed to but now I believe I should ask which country you have switched to?” Fortunately he likes me and I can get away with this especially if you bring back something better than what he commissioned. But I still couldn’t get the Syria film commissioned until I had delivered the Yemen film and as I’d spent so much time finding it I had no budget left to pay for an edit so money made from my dangerous Channel 4 news films in Syria would pay for the Yemen edit. I couldn’t afford the great Ollie Huddleston whom I’d worked with on every film so far so this was the first departure working with a close friend who’d helped in the edit of The Liberace of Baghdad and Japan (in fact he edited the Japan film in the end when I ran out of time and money for Ollie on this film.)

So I would climb into the crammed loft of Johnny Burke, a Tai Chi teacher living in North London who departs from his meditative life to edit only with me (he hates TV) we would cut on his iMac between his Tai Chi classes and between my flying off to now war torn Syria editing Yemen over 11 random months including my week in a Syrian prison for my sins.

On my release from prison I met with the BBC to show them a rough cut of Yemen and tried pushing my Syria film, (now Amer’s wife Ragda was out of prison and also in the film, added to which I’d gone to prison and entered the film) – Channel 4 had rejected the film as being too newsworthy (ironic after Syria being so un-newsworthy) BBC2 had rejected it because it wasn’t newsy enough, Nick was my only chance but unfortunately the BBC4 Arab Spring season didn’t happen and Nick Fraser said he “Couldn’t justify commissioning it without an Arab spring season.”

In the same week I was told that the material from my Syrian project had rated No1 in the USA ITVS call where film from 166 countries compete for ‘completion’ money, so maybe I’m not going completely mad after all. I’m still waiting for final confirmation from ITVS and also have the PBS series called Frontline interested in the Syria film, fingers crossed. Amer and Ragda are now in Lebanon after my arrest from where I filmed them and their ongoing story. A twist in their twisted love story was that she recently left him and the family in the safety of Beirut to go back to Damascus and fight, feeling torn between her loyalties to the family and loyalties to the struggle. I hear now that she has returned home again though and I am overdue another visit but awaiting some funding really.

Jude: At one point you were encouraged by potential commissioning editors to go to Dubai with the possibility of making a documentary there. What were your impressions of Dubai and why were you not inspired to make a film there?

Sean: Nick Fraser had just returned from a lavish all paid business class trip to Dubai Film Festival, he’d witnessed the sheikh’s fruit juice reception where as soon as the formalities were over the booze and women were brought in and he thought this would be a great place for me to make a film. I went along with him but never really believed in it. I hated the place and the people that live like that. My work in the Arab world is to spread a positive vibe about Arab people who are so often misunderstood by the media. I felt that my making this film would be falling into the same trap as other foreign film-makers. In the end of course I found myself somewhere completely different; even in Dubai I ended up with the Indian slave workers on the outskirts of the city sleeping 10 to a room, but here I couldn’t get real access to their plight and felt like their lives there were almost pornographic, I wasn’t sure why I was there or what I was doing there and by now I’d seen something much more interesting in Damascus where my heart was set. Plus Dubai was impossibly expensive on a BBC slave budget – the cheapest hotel was like £60 a night and in Damascus I paid £5.

Jude: Did you envisage the strife that is now tearing Syria apart back when you first started spending time in Damascus?

Sean: No I didn’t imagine it, even when I was in Yemen filming there and seeing it happen there, I kept saying “This will never happen in Syria” then when it started I figured the president (Bashar al-Assad) would do a deal with the opposition. The most confusing aspect of my time in Syria was trying to gauge the people’s feelings about the regime and I concluded that the president had a great support in the country. Even in March, April, even May 2010 Syrians were not asking for Assad to go but to implement the reforms he had promised since 2000 when he took office. Of course the carnage that we see today is the truth of the regime, now hanging the dirty -washing clear for the world to see. The well-groomed-western-educated-eye-doctor image is no more, now al-Assad is open and honest finally to the world, a monster like his father and brother and one hopes should meet the same destiny as Gadaffi.

Jude: Considering the fact that Syria is now in the news so much, why do you think you’re still finding it so hard to get your Syrian documentary commissioned?

Sean: I don’t know, Nick Fraser turned it down a couple of weeks ago saying he ‘Could not justify it without an Arab Spring Season.’ A BBC2 series called ‘This World’ got close to commissioning it until they met me. Then they backed off saying Panorama were doing something, in fact Panorama have done 2 films on Syria in the last year or so, I have been filming this for over 2 years so far… it is a human story that has never been told yet since the Syria conflict began…maybe TV is changing but I know the great British public are crying out to connect with these places through people instead of grainy you tube footage that just looks the same in the end.

Jude: You were detained by the secret police in Syria, an event which was covered by news teams all over the world. Have you returned to Syria since?

Sean: No. I was deported from Syria which means I cannot return, not legally anyhow. I was in north Lebanon the other week up near the border with Syria and was offered safe passage to Homs with a couple of Syrians there. I wasn’t even tempted!

Jude: Has your detention and what you witnessed had any lasting effects on your state of mind? Does it haunt you?

Sean: I guess it haunts me more than witnessing the massacre in the Yemen film. That doesn’t haunt me, it leaves me saddened – seeing people die and losing their loved ones is horrific, I kind of hide behind the camera there also. In prison I was more shaken by the cries of people being beaten and then being befriended by the same guys who were doling out the punishment. They treated me well but I could not understand or accept the way they treated their own and the unbelievable instruments used in torture, including electricity. I befriended my chief interrogators as a way to protect myself but I never knew what new info they would find on me or whether I was really going to get out until I did, so it made a week a rather long time. I want to do a re-creation of it as a drama but when I sit down to write it something stops me going there. I do wake up thinking of incarceration a lot, I don’t like crowds or tight spaces any-more. I feel a little more prone to panic attacks and don’t like being blindfolded; to have the sense of sight taken away is terrifying. I really don’t know how those brave Syrians do it.

Jude: How are the Syrians you befriended during your time in Damascus?

Sean: Some of my friends are still in Syria and others now live in Lebanon. The family I am filming now live in Beirut, where they feel lots safer and where I can visit to film them.

Jude: Are you tempted to go to Homs, where the government are assassinating scores of people as we speak?

Sean: I was in Homs before I left Syria but this was before it became a blood bath massacred town, it was known as the heartbeat of the revolution when I visited, where the protests were happening in a carnival-like atmosphere daily and nightly. The government used the idea of foreign fighters in the country as an excuse to make this disgusting attack.

Jude: Do you think Homs is going to be looked back on in years to come as Srebrenica is now?

Sean: Yes or like Hama was viewed in the 80s – a place where a whole town was encircled and bombed-to-bits killing a reported 30,000 people – I can’t believe in this media age that we can stand by and allow it to happen in Homs. Well we already have I guess.

Jude: How long after visiting Yemen did you meet Kais?

Sean: He met me from the airport, I fell straight into his lap. It felt like the long road that started in Dubai in 2008 was finally coming to a close; the journey had meant something. My films are so fundamentally about character that there can be a revolution anywhere but without Kais or Naoki or Samir or Kev I have no film. In Dubai I watched the economy collapse, it was a great story but I had no character through which to tell it. So I don’t think I was waiting for a revolution but it certainly helped with Kais, it gave my smaller ‘character framed film’ a larger, more global framework, hence its place at Berlin film festival I believe.

Jude: Once the revolution got under way, were all the normal services open? Could you just go to a bank and draw money out for food or did you have to carry cash with you everywhere?

Sean: ATMs worked OK in Yemen funnily enough but not in Syria, there was a blockade put on all money transfers as part of the western sanctions, so I needed to carry bundles of cash around, which is fine in dictatorships as they are usually crime free, like Japan!

Jude: One of your quotes has always stuck with me, “The best way to get permission is not to ask for it.” In the hospital scenes in Yemen: Reluctant Revolutionary, did you not ask for permission to film in the hospital, did you just walk in? How did you get access?

Sean: I walked in with Kais, to be honest I hesitated and tried to retreat because I knew what was happening but a doctor pulled me over and asked what network I was. I said BBC, he pulled me in with Kais and took me through the hall and into intensive care where the dead and dying were being dragged, in this situation they want exposure – there is no asking. Then as the injured lay dying at first I felt terrible to film them but then I learned that it is what they want in their last moments of life. They don’t see you as an outsider, they see you as one of them taking the risks to tell their story. All the same I found it strange filming the young boy dying and the boy holding the hand of his brother. It isn’t easy and you cannot really ask in that situation either. You just respond.

Jude: How did witnessing so many deaths affect you afterwards?

Sean: I don’t know it is in me somehow and always will be, I was more shocked when coming out from the intensive care room to go to the toilet to discover they had dropped the bodies in this area and I needed to clamber over then to take a piss. Terrible.

Jude: In the film you were chewing the drug khat leaves in several shots, a social drug widely used amongst the Yemen but in segregated gender groups. Did you do this to fit in with the people you were filming or did you genuinely just fancy having some?

Sean: I chewed every day, it helped me get through the day there, life outside the camp in Yemen was quite boring for me so this helped, especially when sitting in a big room with men only. In the end I put vodka in my water bottle which gave an even bigger kick.

Jude: What is khat like? Did you ever do the full cheek-pouch job with the khat?

Sean: I would get mouth sores and swallow too much of it – it’s a real knack to keep it in your cheek, I never really got the knack of it and didn’t really miss it when I didn’t have it.

Jude: At one point, in Change Square in Sana’a as the protests escalated into revolution, you’re seen posing as a tourist, wearing a goofy grin and a silly hat, in order to protect your identity as a filmmaker. Despite this you attracted the attention of the secret police. Were you not frightened?

Sean: I got frightened after we filmed the massacre scene – by this time all foreign journalists were kicked out and I was the only witness to the massacre with a camera from foreign media so not only did it feel important for me to show it but I sensed it was as important for them to make sure it wasn’t seen; we didn’t know who was a spy and not in the camp. The first difficulty was getting out of the camp that night without losing the material (which we managed), the next was getting out of the country. To this day both my cameras are still in Yemen, it was just too dangerous to leave with them, anyway it is an excuse to go back (hopefully with my kids) to get them soon.

Jude: How did you feel about being told by the guy in the hotel that another cameraman had been killed in the camp and it was now very dangerous for you to go back into the camp?

Sean: This was a tense time but critical for the film, it is why I included the shot of my son talking to me on the phone, his words of wisdom stand out still, the most sensible words in the film many tell me – it is the critical point that anyone with a family feels, going into danger when you have kids at home. I don’t have an answer except that is what I am there to do. But I left pretty sharpish after it to be with my kids!

Jude: The subjects of many of your films have much in common – big hearted men with a great sense of humour in deep shit due to the environment and social situation in which they live; Kevin Rudeforth (now your webmaster) in Working for the Enemy, Samir Peter in The Liberace of Baghdad, Naoki Sato in Japan, A Story of Love and Hate, and now Kais in Yemen: Reluctant Revolutionary. You are under constant scrutiny for the fact that you don’t live your life in the traditional family man role, but instead spend months abroad searching for and making documentaries in countries facing bleak hardship. Is there a connection? Are these men you seek out, befriend and film, in some way surrogate Seans?

Sean: Yes they are all surrogate Seans I guess, I am working stuff out about myself in all my films as well as exploring themes and things I face in my everyday life so I can honestly connect with the people I film. I don’t really expose my issues to them until after the filming process I guess, but they feel an empathy and connection and know I am from a similar walk of life or at least mind set to them. It is a conscious choice in order to find people that connect with my target audience over in the West, people who wouldn’t normally connect with the Arab world but when they meet people like my subjects they do; open honest guys who share their feelings and fuckedupness; it makes the big messy world smaller somehow.

Final words from some of his documentary subjects on Sean:

Kais Ahmed (The Reluctant Revolutionary): This is from my heart. I met this gentle man Sean McAllister firstly via internet by emails and chatting via Facebook via friends in Syria – they told him about me and they told me that he wanted to film my story with my old hotel, Sana’a Nights, then we met I believe December 2010.

My first impression was scared – what and who is this person Sean? Will it be good for me to get filmed by him? I had many fears but when I met him and I get to know him I felt he is not just film maker, he is an angel. I mean it, he is, he lived with me filming me what I do where we go and when you get to know Sean McAllister you find out he is great man with great feelings he is not just film maker he is a hero too because he pushed me to the Youth Revolution in my country Yemen and he opened my eyes to freedom and true life. I will never ever forget this person the one who changed my negative life into positive life. Sean suffered a lot of being chased by intelligence in Yemen, me too I got bad experience with them, but Sean McAllister he is one of the heroes in Yemen. Not just film maker. He is great film maker.

After the film I feel like new person really I was reluctant but not any more the film that Sean made in Yemen made me feel that the life and the change will never come by sitting at home but by moving ahead with everybody to the right path and freedom. My feelings is great and I hope the film will be seen in all over the world. Sean Mcallister I’m saying you are great man keep on filming you are the right man. Thank you my friend and God Bless You.

Naoki Sato (Japan: A Story of Love and Hate): Sean is my most important friend that I’ve had, the most reliable in the world. As for the Japanese, they see Westerners as having no modesty, and yet for the first time I saw foreigners being polite about Sean. Sean is more of a conservative character than the Japanese even, I thought he had a Japanese temperament, more so even than Japanese people. He was a silent and reliable personality. Gradually I was more open-minded but it took time.

Kevin Rudeforth (Working for the Enemy): Sean made us feel like we were in a gang, conspiring, making the film together, but he never let us see what he had filmed in case it turned us into performers. It was just us and him, talking about stuff, secrets, just us and that bloody camera, probing, provoking, devouring, he made us question ourselves; we made him question himself. Only the lone camera man can do what he does – a fully armed crew with boxes and lights and bags and cases wouldn’t have got through my front door, literally and metaphorically.

And from his kids, talking about how they feel about his work:

Kate (Ruth and Sean’s daughter, aged 9): I think it’s cool because he has adventures and he brings me and my brothers presents from the country.

Harry (Ruth and Sean’s son, aged 11): I think it’s wicked but I get a bit scared when he’s in these dangerous places. Because anything can happen to him but the good thing is he always comes back safely.

George (Ruth and Sean’s son, aged 13): I don’t really mind, I knew when he was in prison that they would not do anything because he was British, so I wasn’t really scared, but it is annoying when he goes away because everyone needs to be there and Mummy cannot do it all alone.

© Jude Calvert-Toulmin

See the original interview on Jude Calvert-Toulmin’s website